Showing posts with label Scotland. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Scotland. Show all posts

Tuesday, August 1, 2023

‘Don’t be the guy who misses this’

A dedicated cadre of New Jersey brethren have planned a well rounded celebration of Scottish Masonic history for Saturday the 19th. All the details are contained in the graphics. Click to enlarge.

See you there.

Saturday, December 31, 2022

‘Scottish Freemasonry Symposium, Part III’

I’ll wrap up an enjoyable year with this overdue post on the George Washington Masonic National Memorial’s Scottish Freemasonry in America Symposium (the title seems to vary here and there, so I’m going with what’s on the front cover of the program) eight weeks ago. An enjoyable year mostly because of the more-than-the-usual travel, compensating, I guess, for the period of pandemic lockdown. There was Masonic Week in Virginia in February; Royal Arch Grand Chapter in Utica in March; the Railroad Degree in Delaware in April; Masonic Con in New Hampshire in June; and back to Virginia for this conference on November 5—which happened to have been the twenty-fifth anniversary of my Master Mason Degree. That whole weekend was the perfect way to celebrate the milestone.

Professor Emeritus Ned Landsman, of SUNY-Stony Brook, discussed “Mobility and Stability in Scottish Society and Culture in the Eighteenth Century.” The Scottish influx into North America was not as large as England’s, he explained, mostly because the Scots were as likely to emigrate to Ireland and other destinations, and many who did cross the Atlantic were apt to return home after earning some money. But shifting economic and political fortunes in Scotland prompted enough to make the journey to find work, to trade, and to secure greater freedom. In the eighteenth century, it was Highlanders mostly, representing a “broad segment of intellectual life” (including a number of medical doctors) who established in America societies for sociable, charitable, and convivial pursuits.

Professor Hans Schwartz of Northeastern University in Boston presented “Migration and Scots Freemasonry in America, from the Stamp Act to the Revolution.” Schwartz is a Freemason and, more importantly, he is the liveliest and funniest lecturer I possibly have ever seen. I don’t know his availability to travel to lodges, but if you can book him, you’ll be a hero in your lodge. He explained how Scots lodges in British America were fewer than English lodges, but the Scots were influential beyond their numbers. George Washington’s lodge, Fredericksburg, was a Scottish lodge, as were others in Virginia, such as Port Royal and Blandford. The rolls of their memberships in the 1700s and beyond are filled with Scottish names. In Boston, Lodge of St. Andrew, which met in the Green Dragon Tavern, was the first lodge in British North America chartered by the Grand Lodge of Scotland. In only Fredericksburg and St. Andrew, you have George Washington, Hugh Mercer, Paul Revere, Joseph Warren, Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and a host of lesser known revolutionary patriots and local heroes. And there were Scottish lodges on the length of the Atlantic seaboard, even down into the Caribbean.

Bob Cooper was next, but sadly his talk was cut short. We learned later that he was in pain (his bad knee) and had to get off his feet. From what I can recollect about his talk from eight Saturdays ago, he spoke of the importance of there being a Grand Lodge of Scotland after the union of Scottish and English parliaments as Great Britain in 1707, and that the Grand Lodge served as something of an extension of Scottish nationhood, particularly when it issued warrants to lodges in America.

The fifth speaker was Gordon Michie, another Mason, who spelled out the migration of Freemasonry to the United States, Canada, and the Caribbean. I scribbled some notes, but most of what he told us is well known Masonic history so I won’t transcribe it here. I think the important historical information from Michie’s talk comes from Scottish Masonic Records, 1736-1950 by George Draffen, if you can lay hands on it.

The conference resumed Sunday morning with Heather Calloway, Executive Director of Indiana University’s Center for Fraternal Collections and Research, who spoke on “Aye, Right Beyond the Haggis Dinners, Old Nessie, and Yonder in America.”

Speaking from not only a Masonic perspective, but from a broader American fraternalism outlook, she told of how Scottish culture was filtered into America through certain fraternal orders, like the Benevolent Order of Scottish Clans, the Daughters of Scotia, and others. (Back in the day, there were more than 300 fraternal societies in this country, with aggregate membership of about 6 million, she said.) Heather shared a few anecdotes, including one of a visit to Federal Lodge 1 in the District of Columbia, which invited her to look at some “cool old stuff.” The lodge didn’t know it had one particular item they found in a closet: the Bible used at George Washington’s funeral.

And the final presentation brought to the lectern Ewan Rutherford, Deputy Grand Master of the Royal Order of Scotland, who gave a Scottish history of Freemasonry. Beginning in 1475, with the incorporation of masons in Edinburgh, and continuing through more familiar facts about William Schaw, the Mary’s Chapel minute book, and to the Royal Order of Scotland, Rutherford brought the affair to a tidy conclusion, making clear how Scotland has been central to the identity of Freemasonry.

This actually is the third in a series of Magpie posts about the events, and there are sidebars also, if you care to scroll through the posts from November. Pardon the poor quality of the photographs. So, here we go.

At the Washington Memorial, introductions, welcomes, and remarks were tendered by Executive Director George Seghers, President Claire Tusch, and Director of Archives and Events Mark Tabbert. The roster of presenters was a balance of Masonic and non-Masonic speakers who gave explanations of how Scots impacted British North America by emigrating to the colonies and bringing their Freemasonry with them. I think it is a neglected subject thanks to our anglocentric understanding of early American history. We think of things “Anglo-American” at the exclusion of the Scottish people, philosophies, religion, and more that also came to the American colonies.

|

| Professor Ned Landsman |

|

| Professor Hans Schwartz |

|

| Bro. Bob Cooper |

Next up was Jim Ambuske from the Center for Digital History, Washington’s Library, at Mount Vernon, who brought to light an aspect of American Revolution history unknown to most. He explained the War of Independence as a civil war among Scots living in America. Citing a family named McCall as an example, Ambuske explained how Archibald McCall settled in Virginia in the 1750s and became a successful merchant and farmer. Politically, he sometimes sided with Washington and Jefferson, but he also supported the Stamp Act. When the war started, he placed himself on the side of the Loyalists, and so the rebels deemed him a traitor and eventually seized his properties. McCall appears to have been a supporter of Lord Dunmore who, of Scottish heritage, was colonial governor of Virginia and a very active agent of British policy. (When Patrick Henry said “Give me liberty or give me death,” he was speaking at Dunmore.) This was bad enough, but it also put him in the uniquely shameful position of asking the Crown for financial relief due to the loss of his wealth and income. As I understand it, he spent the rest of his life trying to square away these financial disasters, but, in death, he was able to bequeath his daughter two plantations.

|

| Bro. Gordon Michie |

And that was it for Saturday. There was a black tie banquet with a whisky tasting later, but I skipped it, preferring to get downtown for a meal and to duck into John Crouch Tobacconist, Alexandria’s oldest cigar and pipe shop, established 1967. I haven’t been there in ages, and somehow it looks like a smaller shop now that all the floor space is cleared of the Scottish souvenirs and tchotchkes. I bought some pipe tobacco: two ounces of Virginia Currency and, keeping with the Scottish theme, two ounces of Hebrides, a Latakia-heavy mixture that I’m smoking right now.

The conference resumed Sunday morning with Heather Calloway, Executive Director of Indiana University’s Center for Fraternal Collections and Research, who spoke on “Aye, Right Beyond the Haggis Dinners, Old Nessie, and Yonder in America.”

|

| Dr. Heather Calloway |

|

| Bro. Ewan Rutherford |

It was a great event that Claire Tusch, the Memorial Association’s President, said he hoped could be the first of more such conferences. And I agree! (Easy for me to say. I don’t have to do any of the work.) But I’ll be back in Alexandria in February for the Memorial’s centennial anniversary celebration. More on that later.

I’m sorry for the lack of content and detail on the presentations, and, as always, any errors or omissions are attributable to me.

Happy New Year!

Labels:

GWMM,

Heather Calloway,

pipe smoking,

Robert L.D. Cooper,

Scotland,

tobacco

Wednesday, September 7, 2022

'Remembering John Skene from Aberdeen'

I have to catch up on my reporting of a few terrific events here and there recently. The following is a recap of a celebration of Masonic history that took place in New Jersey on August 27.

Brethren from around New Jersey and beyond converged on the Peachfield historic site in Westampton on the afternoon of August 27 to honor the memory of the first Speculative Mason to arrive in North America.

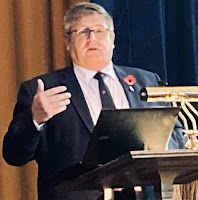

|

| Bro. Robert Howard |

“Coming of age when religious turmoil was the norm, John Skene’s membership in the Society of Friends provided him anything but the peaceful and pacifist existence that we associate with Quakerism today,” said Bro. Erich Huhn, of New Jersey Lodge of Masonic Research and Education 1786 and a candidate for a doctorate in history at Drew University. “The Friends were persecuted throughout his childhood, and, as Skene reached adulthood, he held true to his convictions. As a Quaker, he was persecuted and imprisoned throughout his life in Scotland. In the typical ebbs and flows of seventeenth century religious turmoil, he faced various periods of imprisonment, freedom, house arrest, and discrimination.”

|

| A wreath was sent by Skene’s lodge, still at labor in Aberdeen. |

Yet, the seventeenth century also was the age of the Accepted Mason, when lodges of operative builders began welcoming men who had no connection either to the art of architecture or to the trade of stone construction. Robert Moray in 1641 and Elias Ashmole in 1646 probably are the best known, but lodge minutes from 1590s Scotland also record the making of Speculative Masons. Skene was initiated into the lodge at Aberdeen approximately in 1670 possibly on account of his being a merchant and a citizen prominent enough to be made a burgess there. His being a Quaker raises the question of his taking a Masonic oath, but again history is silent on details.

|

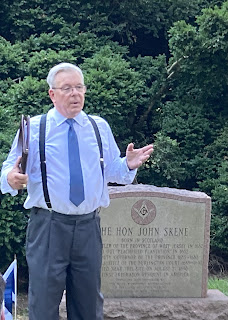

| Bro. Bob Cooper |

Arriving in West Jersey, Skene purchased 500 acres from Governor Edward Byllynge and founded his plantation, which he named Peachfield. Not long thereafter, Byllynge appointed Skene the Deputy Governor. Seventeenth century colonial records being what they are, it is not known how Skene earned the appointment, but the land acquisition preceding it could not have been meaningless. Another quirk of history emerges when Byllynge was succeeded as Governor by Dr. Daniel Coxe, the father of Provincial Grand Master Daniel Coxe, who was appointed by the Grand Lodge of England in 1730 to govern Masonic affairs in New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania.

|

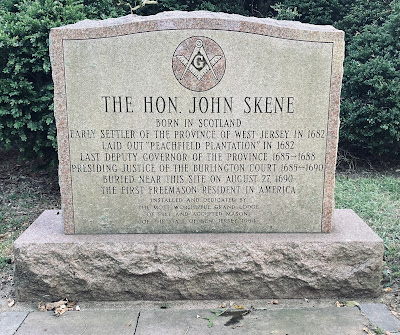

| Dedicated in 1984 by the grand lodge, this stone stands on the land John Skene owned, Peachfield. A different calendar was in use during the seventeenth century, so to commemorate Skene's death, you have to play along. |

After Skene’s death circa 1690 (accounts of the year vary), his widow gradually sold off tracts of the Peachfield plantation. All that remains today is a stone house built 1725-32, which was damaged by fire in 1929 and restored in the early 1930s, situated on 120 acres. The property is only three miles from the Masonic Village at Burlington. In 1984, the local grand lodge dedicated a headstone memorializing this historic Brother Mason. The exact location of his burial place is unknown, but August 27, 1690 is the date of death engraved in the stone.

|

| Bro. Mark and Bro. Glenn. Look for them on YouTube. |

The event on August 27 featured many participants. Assisting emcee Bob Howard was W. Bro. Christian Stebbins. Leading prayers were RW Glenn Visscher and RW Eugene Margroff, with RW Mark Megee reading from Scripture. Bro. David Palladino-Sinclair of the Kilties serenaded the group with his bagpipes, performing “Flower of Scotland,” “Scotland the Brave,” and “Amazing Grace.” A wreath was placed at the gravestone by Cooper and the Worshipful Masters of both Eclipse and Beverly-Riverside, Patrick Glover and Frederick T. Ocansey, respectively. In his closing remarks, RW Bro. David Tucker, Deputy Grand Master, told the assemblage that looking to the past for role models helps take our focus off ourselves, and that it is fitting to salute John Skene for being the earliest Freemason who deserves credit for helping establish the fraternity in New Jersey.

|

| Bro. David Palladino-Sinclair |

Also traveling some distance was Mark Tabbert of the George Washington Masonic National Memorial in Virginia, who told us of the Scottish Freemasons in America conference there in November.

The celebration of Skene was not over yet. The group caravanned to Mt. Holly Lodge 14 for a catered dinner replete with Masonic toasts following a tour of the historic building.

Peachfield is owned and operated by the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the State of New Jersey, which makes the site its headquarters. Tours, including for groups, can be arranged by phoning 609.267.6996.

Labels:

cemeteries,

Erich Huhn,

John Skene,

Mark Tabbert,

New Jersey,

Peachfield,

Robert L.D. Cooper,

Scotland

Sunday, March 27, 2022

‘Bob Cooper on early catechisms’

|

| Robert L.D. Cooper |

Cooper, I think we can say, is the dean of Scottish Masonic historians. He is a Past Master of Lodge Sir Robert Moray 1641, and also of Quatuor Coronati 2076, the premier lodges of Masonic research in Scotland and England, respectively. He is an author of very useful and accessible books for Masonic readers, including The Masonic Magician, about Cagliostro; The Red Triangle, a chronicle of anti-Masonry; and Cracking the Freemason’s Code, among the best primers on the fraternity to emerge during the first decade of this century. You could dive safely into any of his books, and I recommend The Rosslyn Hoax? to anyone stuck on the Templar nonsense.

His topic at Eclipse Lodge was intriguing: “Early Freemasonry 1598…or Freemasonry Before 1717.” I think that period is without form and void in the minds of most Freemasons in the United States. Despite the centrality of Scotland to Freemasonry’s embryonic years, we Americans mostly see the Craft as having been born in early eighteenth century London, but the scant evidence are tantalizing pieces of the same vexing puzzle. Bob’s overall point was to walk us through the catechism of the Edinburgh Register House Manuscript, which he terms the oldest Masonic ritual, dated 1696. To get there, he had to present historical context first, so he tied together for us the Art of Memory, Hermeticism, William Schaw, and the need for an illustrative catechetical ritual to teach illiterate stone masons the secret education that goes well past mere modes of mutual recognition.

Needless to say, he did so convincingly and in only about an hour. Click here to read this seventeenth century catechism. You’ll see many things that are foreign to your lodge experience, but it’s amazing how much is fitting or at least familiar enough.

For more on the Art of Memory, see the Frances Yates book.

Friday, August 20, 2021

‘Scottish Freemasons in America’

It’s never too early to plan on attending a great event in Freemasonry, so look ahead to next November for a very promising weekend at the George Washington Masonic National Memorial in Virginia. A multi-faceted affair called “Scottish Freemasons in America, 1750-1800” is scheduled for November 4 to 6, 2022.

You’ll come for the food. You’ll stay to see Tabbert in a kilt.

A symposium starring presenters from the academic and Masonic worlds will bring to life the story of Scottish Freemasonry’s role in giving shape to the Craft here in America.

Did you know the lodge in Fredericksburg, Virginia, where George Washington was made a Mason, was a Scottish lodge? Well, it was—at least once it finally received a warrant from Scotland years after Washington was raised.

This amazing weekend will include a visit to that lodge, and some of you may have noticed it’ll coincide with the 270th anniversary of Washington’s Master Mason Degree.

The featured speaker will be Bro. Robert L.D. Cooper, Curator of the Grand Lodge of Scotland and author of books you really ought to have read by now.

Also planned are a whisky tasting, Scottish cooking, and more.

For more information, contact Bro. Mark Tabbert, the Memorial’s Director of Archives and Exhibits here.

Labels:

George Washington,

GWMM,

Robert L.D. Cooper,

Scotland

Monday, May 15, 2017

‘Esoteric Quest to Scotland’

|

| Courtesy NY Open Center |

If I weren’t prohibited by law from leaving the country—I know too much—I’d join this year’s Esoteric Quest (New York Open Center’s travel bureau) to Scotland. No reason why you couldn’t go though. From the publicity:

An Esoteric Quest

in the Western Isles of Scotland

Megalithic, Norse and Hermetic Culture

in the Celtic World

Stornoway, the Outer Hebrides

August 22-27, 2017

Scotland is one of the most esoterically rich countries on earth. The rock of the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides is some of the oldest anywhere, and the island is dotted with enigmatic megalithic sites, most famously Callanish, that echo an ancient culture. Lewis is also a place inhabited by Picts, Scots, and Vikings, where Gaelic is still spoken.

|

| Courtesy NY Open Center |

We invite you to join us on this Quest and participate in one of the most highly regarded series to be found anywhere on the planet on the half-forgotten spiritual history of the West.

Pre- and Post-Conference Journeys:

Callanish, Scotland

Findhorn, Scotland

Westfjords, Iceland

There will be a pre-conference day visiting the megalithic sites on Lewis and Harris, and two Post-Conference Journeys: one to the celebrated eco-village and spiritual community of Findhorn, followed by three days on the most sacred of all Scottish islands, Iona. The other will return to the expansive grandeur of the Westfjords of Iceland, a realm of cosmic ocean vistas, ever present rushing waterfalls, and immense, profound silence.

A brochure and more info here.

It seems registration is not yet open, but I will update this when that happens.

Wednesday, September 23, 2015

‘ICHF 2017?’

It was announced at the 2011 International Conference on the History of Freemasonry in Alexandria, Virginia that the next conferences would be hosted in Edinburgh in 2013, Toronto in 2015, and England in 2017, that being the tercentenary of the Grand Lodge of England. This year’s event did not come to fruition due to financial obstacles, and it was announced today by the Grand Lodge of Scotland that it is weighing the concept of hosting a smaller event (date TBD) in Scotland that would be “more focused on Scottish Freemasonry,” indicating ICHF 2017 in England is not to be.

|

| Courtesy GLS |

As for England in 2017, as reported months ago in the pages of The Journal of The Masonic Society, Quatuor Coronati 2076 will host a tercentenary celebration at Queens’ College, Cambridge next September. Planning is advanced by now (call for papers, etc. was long ago). I’ll share news of this as it becomes available.

Labels:

GL of Scotland,

ICHF,

Masonic Society,

QC2076,

research,

Scotland

Friday, September 5, 2014

‘Swedenborg, Yeats, and Freemasonry’

Flashback Friday is an occasional feature on The Magpie Mind when I finally get around to writing about something I should have covered a long time ago. Today we travel to 2010 when the Chancellor Robert R. Livingston Library of the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of New York hosted Marsha Keith Schuchard, an authority on the subjects of Emanuel Swedenborg, William Butler Yeats, and Jacobite Freemasonry. The lecture also was sponsored by the W.B. Yeats Society of New York and the Swedenborgian New Church.

|

| Keith Schuchard November 8, 2010 |

She has appeared at the lecterns of several Masonic venues, including Quatuor Coronati Lodge No. 2076. Her thesis is so original, as if to appear from out of the ether, so without further preamble, a flashback to November 8, 2010 in New York City. What follows is a greatly shortened version of the lecture. Any concerns of error by omission are attributable to me.

Swedenborg, Yeats, and Freemasonry

I am grateful to officials of the New York Yeats Society, the Livingston Masonic Library, and the Swedenborgian New Church for inviting me to give this lecture, and I will try to address the interests of all three groups. In the process, I will be moving back and forth from the 18th to the 20th centuries, as I trace the role of Freemasonry in the lives of Swedenborg, Yeats, and their contemporaries. It will be a complicated trail to follow, but I hope it does not become the dreaded Hodos Chameleontos, the “Path of the Chameleon,” which Yeats described as confusion, multiplicity, and unpredictability. With that caveat, let us head down the trail.

|

| William Butler Yeats in 1903. |

This long-running melodrama was fueled by the 18th century political rivalries between “ancient” Jacobite-Tory and “modern” Hanoverian-Whig Masonic systems, with the first maintaining loyalty to the exiled Stuart royal family, and the second to the Hanoverian kings who have ruled Britain from 1714. Jacobite exiles and their multi-national supporters developed new Écossais systems, with increasingly elaborate Kabbalistic, Rosicrucian, and Templar “higher degrees,” while Hanoverian-Whig systems maintained more rationalist-Newtonian interests. Though the long dominance of Whig-Protestant historiography in the academic world meant that international Jacobite Freemasonry almost disappeared from the historical record, new generations of revisionist historians in Britain and Europe are bringing this submerged history to the surface. In the process, the important role that Protestant-Lutheran Sweden played in supporting the Jacobite cause is emerging from the historical shadows, especially from unpublished documents preserved in the Stuart Papers at Windsor Castle and international diplomatic and Masonic archives.

Though conventional academic wisdom long claimed that the Stuart cause was dead after the defeat of “Bonnie Prince Charlie” on the battlefield of Culloden in 1746, a study of Swedenborg’s political-Masonic career from 1710 to 1772 and of Mathers’ and Yeats’ political-Masonic experiences from 1888 to 1918 reveals the surprising survival of the Jacobite cause and of the old Jacobite-Hanoverian Masonic rivalries into the early 20th century. In a forthcoming book, Emanuel Swedenborg, Secret Agent on Earth and in Heaven, I will argue that Swedenborg was employed as a secret intelligence agent and financial courier for the pro-French, pro-Jacobite party of “Hats” in Sweden, who opposed the pro-English, pro-Russian party of “Caps.” In undertaking this dangerous, clandestine role, Swedenborg was motivated by genuine, even heroic, patriotism, while Sweden was threatened by defeat and even dismemberment by her powerful enemies. In the process, he and his political allies utilized Franco-Scottish or Écossais Masonic networks to carry out their political, diplomatic, and military agendas.

From the time of his first visit to London in 1710-1713, when he was reportedly initiated into a Masonic craft lodge, until his death in London in 1772, Swedenborg and his family were involved in pro-Jacobite, anti-Hanoverian activities. Curiously, some of the most dramatic moments of his participation took place in 1744-1745, when MacGegror Mathers claimed that his Scottish ancestor was taking part in the same enterprise. I will now give some examples of Swedenborg’s Kabbalistic meditations and Jacobite-Masonic predictions, when he undertook a dangerous intelligence mission to London, where government agents were desperately looking for supporters of a feared Franco-Swedish-Jacobite invasion. Before he left Amsterdam for England, Swedenborg was prepared both mystically and Masonically for his Jacobite mission.

In April 1744, while living in Holland, Swedenborg recorded in the peculiar language of his dream diary his initiation into the Jacobite high degrees of Masonry: “I was first brought into association with others... I was bandaged [blindfolded] and wrapped. I was inaugurated [initiated] in a wonderful manner. And then it was said, “Can any Jacobite be more honest?” So at last I was received with an embrace. Afterwards it was said that he ought by no means to be called so, or in the way just named… It was a mystical series.”

The word “honest” was used by Jacobites to denote faithful and discreet supporters, but his initiators worried that the word “Jacobite” was too explicit, because they were worried that Hanoverian spies had penetrated their lodges. Feeling pressured by the demands for secrecy and fearful of the risks involved in his upcoming journey, Swedenborg recorded his dreams and visions about the secret enterprise: “It seemed to me that we worked long and hard to bring in a chest, in which was contained precious things which had long lain there; just as it was a long work with Troy; at last one went in underneath and eased it onwards; it was thus gotten as conquered; and we sawed and sawed...” Wilson Van Dusen, editor of the diary, observes that Swedenborg’s reference to Troy is most curious, for the Trojan horse contained soldiers who opened the enemy gates and enabled the town to be conquered: “It is the same here. The chest contains something precious that will enable the ‘town’ to be conquered.” At this time, Swedenborg was staying with his close friend, Joachim Fredrick Preis, Swedish ambassador at The Hague, who had long participated in Jacobite schemes and who was currently facilitating the shipment of Swedish cannons through Dutch canals en route to the Jacobite forces in Scotland. Preis also helped the recruitment of Swedish soldiers serving in French regiments to join Prince Charles Edward Stewart in the planned campaign. They could indeed provide a Trojan horse to conquer the city of London.

When French political bickering and fierce storms stalled the invasion, Swedenborg laid low in London. He began writing a strange messianic treatise, in which he used Scriptural passages to predict the actions of the Jacobites and their prince to restore the Temple of Jerusalem in the North. Anti-Scottish propaganda had long identified the Scots with the Jews, while pro-Jacobite propaganda utilized quotations from Hebrew scripture in their coded correspondence. The theme of exile for Jacobite and Jew was a potent reminder of a shared fate and a call to action. It would not be beyond the paranoia (now justified) of the government decipherers to read Biblical lines as referring to Jacobite forces coming from Ireland (west) and Sweden (east), with the Stuart prince landing in Scotland (north) and the invasion coming from France (south). The main Jacobite prisoner in London was Sir Hector Maclean, former Écossais Grand Master and major planner for Sweden’s participation in the projected invasion. Maclean was held in the Tower of London, close to Swedenborg’s current residence. The Swedish Hats feared that he possessed incriminating papers about their complicity, and they pressured the Jacobites to arrange his escape. At this time, in 1745, an anti-Jacobite exposé, titled The Freemasons Crushed, revealed that a new, elite grade of Jacobite Masonry included “a tapestry with the image of a ruined temple representing decayed Freemasonry which the Scottish Masters will regenerate.” Swedenborg seemed to refer to the new Écossais degree of Architécte, when he portrayed a Jewish architect who envisions the new temple:

“Upon an exceeding high mountain...was the building of a city. There he saw a man having in his hand a measuring line. A wall surrounded the temple without, and he measured all the things... The splendor of Jova came into the temple by way of the gate looking to the east—he showed the place of the throne... The prince he shall settle in the sanctuary—the northern gate.” Swedenborg’s words would soon prove prophetic. However, by late July 1745, he sensed he was in great danger in London, and he abruptly departed just before the arrival of the Stuart prince in Scotland.

|

| Charles Edward Stuart Bonnie Prince Charlie |

|

| Gustav III King of Sweden |

Despite the secrecy of their meetings, the British ambassador in Florence (Sir Horace Mann) was able to suborn a French member of Gustav’s entourage and thus learned about the Masonic agreements. In the 1730s, Mann had been a member of the Hanoverian lodge in Florence, which was closed down because of the Papal Ban of 1738. After that, despite Mann’s vigilant surveillance over the Jacobites, he could learn little about developments in Écossais Masonry. On December 30, 1783, he wrote to John Udny, English consul in Leghorn, a revealing letter, which expressed his scorn for “ancient” Stuart-Templar traditions of Freemasonry: “His Swedish Majesty...has taken other steps, which though they may appear ludicrous, are not less certain. It is supposed that when the Order of the Templars was suppressed and the individuals were persecuted, some of them secreted themselves in the High Lands of Scotland and that from them, either arose, or that they united themselves to the Society of Free Masons, of which the Kings of Scotland were supposed to be hereditary Grand Masters. From this Principle the present Pretender has let himself be persuaded that the Grand Mastership devolved to him, in which quality in the year 1776, He granted a Patent to the Duke of Ostrogothica [sic] by which he appointed him his Vicar in all the Lodges in the North, which that Prince some time after resigned as many of the Lodges in those parts for want of authentic proofs, refused to acknowledge the pretended Hereditary Succession to that Denomination. Nevertheless the King of Sweden during his stay here obtained a Patent from the Pretender in due form by which He has appointed His Swedish Majesty his Coadjutor and Successor to the Grand Mastership of

all the Lodges in the North, on obtaining which the French gentleman [Mann’s spy], whom I have often mentioned in my late letters, assured me that the King expressed the greatest joy.”

Mann went on to describe Gustav III’s plan to solicit funds from Templar Masons to support their Stuart Grand Master. He also noted the continuing negotiations of Baron von Wächter in favor of the rival Strict Observance German Masons. In 1788, after the death of the no-longer “bonnie” Prince Charlie, the Masonic documents were sent to Gustav III, and the temple was indeed restored in the North—just as Swedenborg envisioned 43 years earlier.

While Gustav and Carl immersed themselves in occultist studies and experiments, they also developed Swedish Freemasonry from a Jacobite support system into an instrument of state. The king’s confidante Schröderheim described this potent mystical-political brew: “In a small circle of brethren that gathered around the king and the duke more noble objects for our works occurred. They embraced religion, communion with the underworld, with spirits, politics, morals, and alchemy.”

In 1839 in Scotland, there was a revival of the Royal Order of Heredom of Kilwinning, an 18th century Jacobite Masonic order, which had maintained close relations with Swedish and French Freemasonry. The 19th century Scottish members re-established ties with Swedish Masons, and as the great occult revival emerged in the 1880s, some Irish and Scottish nationalists began to dream that the “ancient” Écossais Freemasonry, enriched with Swedenborgian rituals, could play a political role in the growing independence movements in Ireland and Scotland. Thus, we enter the theatrical epilogue of the Masonic melodrama in which Swedenborg and his collaborators earlier played such intriguing but secretive roles.

In 1843 in Edinburgh, there was also a revival of the “Religious and Military Order of the Temple,” which caused a public controversy. Arguments about the reality of the Order of the Temple provoked new interest in 18th century Jacobite Freemasonry, which was further fueled by the romantic publications of the Sobieski Stuarts, two brothers who claimed to be the illegitimate sons of Charles Edward Stuart. In Tales of the Century (1847), they reported that the prince secretly visited Sweden ca. 1750, where he was welcomed by the Freemasons, who honored him as their leader. Despite accusations of fraud, the Sobieski brothers were treated royally by staff at the British Museum, where tales of their charismatic presence may have influenced MacGregor Mathers’ Jacobite fantasies.

As the neo-Jacobite Masonic movement began to emerge among Scottish antiquarians, it was paralleled by a neo-Swedenborgian Masonic movement among a small number of British and American initiates. The driving spirit was Samuel Beswick, who was born into a Swedenborgian family in Manchester, England in 1822. Because several important Swedish Masons who were Swedenborgians had lived in Manchester in the 1790s, it is possible that Beswick’s family became privy to Swedish oral traditions about Swedenborg’s Masonic affiliation. After moving to the United States and Canada, Beswick promulgated “The Primitive and Original Rite of Symbolic Masonry,” which he claimed to be based on earlier Swedenborgian rituals. Though his book The Swedenborg Rite and the Great Masonic Leaders of the Eighteenth Century (1870) is a frustrating mix of valuable fact and unverifiable speculation, he managed to attract several British members of the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia, which was restricted to Master Masons. From manuscripts describing the 18th century Swedenborgian rituals, Mathers would subsequently develop the elaborate symbolism and ceremonies of The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in the 1880s.

Through Mathers’ work for Golden Dawn, W.B. Yeats emerged onto the neo-Jacobite, neo-Swedenborgian, neo-Rosicrucian stage. Though Golden Dawn was not a Masonic organization, many of its members were Masons, and it drew heavily on Masonic symbolism and rituals. While Mathers was a Freemason, his co-worker Yeats maintained a much more ambiguous and troubled relationship with the fraternity.

Yeats was initially so attracted to the Kabbalistic expertise of Mathers that he was secretly drawn into his Jacobite activities, such as a brief association with the “White Rose” societies which worked for a Stuart restoration. He wanted to believe that his Protestant ancestors fought with the Jacobites in 1689 at the Battle of the Boyne where, he lamented, the Williamite victory had “overwhelmed a civilization full of religion and myth.” And he convinced himself that he was descended from James Butler, Second Duke of Ormonde, the Anglo-Irish Freemason who helped plan the Jacobite rebellion of 1715 and the Swedish-Jacobite plot of 1717. These fantasies were reinforced by his attendance at a Requiem service for “Bonnie Prince Charlie.” The Neo-Jacobite revival in the 1890s was strong enough to draw the attention of international journalists, who recognized the vulnerability of the German-derived dynasty in Britain.

Echoing 18th century Jacobite complaints about the Electors of Hanover who became kings of Britain, Mathers and his more militant White Rose colleagues argued that Queen Victoria and her Saxe-Coburg-Gotha line were German usurpers. They provided military training to their initiated brethren and dreamed of raising a “Celtic Empire” that would embrace Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany. Newspapers all over the world carried stories on the international “legitimist” campaign, which sought to counter the rising power of secular, socialist, and communist movements. In headlines ranging from “New Kings on Old Thrones” to the more ominous “Playing at Treason,” journalists made the supposedly dead Jacobite cause seem alive and well.

For Yeats, the best way to harness nationalist energies to the Kabbalistic power of Rosicrucian and Jacobite Freemasonry was to establish an independent “Castle of Heroes” on an island in Ireland. Yeats had “an unshakeable conviction” that “invisible gates would open...as they opened for Swedenborg.” Mathers advised him on the symbolism and rituals, and Yeats worked on the plans for nearly a decade. However, Mathers’ involvement in military planning and arms procurement for the legitimist campaigns led to his ejection from Golden Dawn and his removal to Paris, where Yeats continued to respect his magical expertise but worried about his penchant for violent political action.

In 1906, Yeats visited Scotland, where he gave widely publicized lectures linking Irish and Scottish nationalist ambitions. He then accepted an invitation to stay at Castle Leod in the Highlands, a five-story tower house, originally built in 1606, and the home of the Earls of Cromartie and the seat of Clan Mackenzie. It was to this ancestral home that the old Jacobite, Count Cromartie, returned after his military service in Sweden and India. One wonders if Yeats saw his elaborate certificate of initiation into the Swedish Rite, for Cromartie definitely brought it back to Scotland. Yeats was greatly impressed by Castle Leod, and he wrote “this is a most lovely place—an old castle with wooded hills around it.” He was especially intrigued that ravens still roosted on Raven Rock where, according to Scottish folklore, Gaelic warriors found physical prowess, victory in battle, second sight, and the gift of prophecy. He wrote that the ravens got in the habit “in the time when there were so many fights at it—it is the head of a pass.” From this pass, the Scots held off rival clans and English enemies. Yeats long remembered the ancient Castle Leod and the “joyful youthfulness” of the Countess, and his experience there would color his own dreams of restoring a tower in Galway as a Jacobite-style defense against the madness of sectarian violence. Though he could not get any magical ravens, he would make do with “nine and fifty swans.”

|

| MacGregor Mathers |

After their marriage in 1917, objections to British imperialistic Masonry no longer mattered to the Yeatses, and he and Georgie were still attracted to the symbolism and ceremonies of the Écossais higher degrees. They knew that Mathers had drawn on these when he designed the elaborate rituals for Golden Dawn. They renewed their friendship with Mathers widow, who had beautifully illustrated those Swedenborgian-Masonic rituals. When the Yeatses resided in Oxford in 1921, they may even have attended a Masonic lodge. If so, it would be an Écossais or Rose-Croix rite which admitted women. (In 1987, when my husband and I were living in Oxford, the eminent Yeats scholar Richard Ellmann confided to me that he had discovered a note in which Georgie Yeats mentioned their Masonic attendance. Unfortunately, Ellmann became terminally ill and could not locate the note among his voluminous papers. He wanted me to examine her note, because I had been helping him with information on Oscar Wilde’s earlier initiation into a Rose-Croix lodge in Oxford.)

|

| W.B. and Georgie Yeats c.1928. |

As Ireland’s struggle for independence became more violent, culminating in the Irish Civil War in 1922, Yeats worried about his own contribution to the nationalist cause which had generated so much hatred—hatred that now consumed political rivals within Ireland itself. In his great poem Meditations in a Time of Civil War, he drew upon recent, sensationalist publications which charged that 18th century Templar Freemasonry generated the French Revolution. Though Yeats rejected the anti-Semitic argument of the authors, he worried that French secularist, republican Masonry had veered far from its Jacobite and royalist roots. In the last section of Meditations, he wove imagery from architecture and stonemasonry through his lament for the internecine violence, which he summed up in cries of “Vengeance upon the murderers... Vengeance for Jacques Molay.” Referring to the martyred Grand Master of the medieval Templars, he admitted his own earlier attraction to political violence, remembering that:

I, my wits astray,

Because of all that senseless tumult, all but cried

For vengeance on the murderers of Jacques Molay.

Returning to his beloved tower home in Galway, he evoked both the destructive effects of “Loosening masonry” and “cracked masonry,” but also the constructive possibility of visionary architecture and solid masonry—emblems of his hopes for a recovering Ireland.

|

| Nobel Prize for Literature. |

It is from the 18th century Nils Palmstierna’s unpublished diplomatic papers, collated with the Stuart and British diplomatic correspondence, that we piece together the context for Swedenborg’s puzzling claim that he made an important visit to Spain—a visit never mentioned by his biographers. He referred to his earlier journey to Spain in a letter to the Swedish king in 1770, when he asked for royal support against the Caps’ attempt to banish him. A possible explanation for this journey lies in his experiences in Italy in 1738-39. In February 1739, while Swedenborg was in Rome, Nils Palmstierna and Carl Gustaf Tessin, both Masonic Hats, planned a secret diplomatic mission to Spain to solicit Spanish funding for Swedish troops to join a Jacobite invasion of Britain. During Swedenborg’s five-month residence in Rome, he spent much time with Count Nils Bielke, an Écossais Mason. Named a Senator of Rome by the Pope, Bielke was close to the Stuart Pretender, James III, and his two sons. British spies reported that Bielke was the main channel for the Swedish-Jacobite overture to Spain and that he collaborated with Carl Gustaf Tessin (his brother-in-law and current Grand Master of Swedish Masonry) in dangerous Swedish-Jacobite intrigues.

In Swedenborg’s laconic travel journal, he described the Roman palace of the Pretender, and a later dream memory suggests that he met with James III and his two sons in the secret chamber arranged for foreign visitors. In March 1739, Swedenborg suddenly left Genoa, Italy, and virtually disappeared. There is no record of his activities for the next two months, until he arrived in Paris in May and sent his confidential reports in the Swedish diplomatic bag to his Hat allies. These letters have disappeared, but they apparently covered his journey to Spain. Unfortunately, his heirs tore out the final pages of his journal, which covered his experiences after leaving Genoa, for they were determined to protect his benign, apolitical public image. However, from Nils Palmstierna’s unpublished papers, we learn that Swedenborg reported to him on his secret mission. Swedenborg later recorded a dream-memory in which money was collected in Spanish chapels or monasteries, which may refer to the Spanish funds which were indeed sent for the proposed (but eventually cancelled) Swedish-Jacobite expedition of 1739-1740.

Nils Palmstierna’s 20th-century descendant, Erik, carried on the family’s diplomatic tradition, and he was a generous supporter of Swedenborgian causes in Sweden. He often collaborated with Mrs. Otto Wilhelm Nordenskjöld, a leading Swedenborgian, whose husband was a direct descendant of the Nordenskjöld brothers who joined Blake’s Swedenborg Society in London in the 1780s and ’90s. As Freemasons with interests in Kabbalah and alchemy, the Nordenskjölds participated in King Gustav III’s Swedenborgian and Hermetic enterprises. Georgina Nordenskjöld’s maiden name was Kennedy, and her own ancestors had served “Bonnie Prince Charlie.” In Stockholm, the Yeatses had tea with Mrs. Nordenskjöld, and the poet was deeply moved by this descendant of Blake’s Swedenborgian colleagues. He declared “his high estimation of Swedenborg,” whose writings made him a convinced adherent of the doctrines of the New Church.” Though he did not belong to any New Church organization in England, “he had intended, when he married, that the ceremony should take place in a New Church temple in London, but circumstances prevented this.” Grateful to his hostess and moved by her history, Yeats may have exaggerated his New Church association, but he increasingly sensed that in Stockholm he was inhabiting an older, unspoiled world, which reflected not only Stuart but Celtic values of art, imagination, and spirituality.

Yeats was especially impressed by the grand architecture of the Swedish royal palace, designed in 1690 by Nicodemus Tessin, whose kinsman, the military architect Edouart Tessin, had been initiated in an Edinburgh Masonic lodge in 1652 and subsequently served the restored Stuart king, Charles II. Nicodemus Tessin was also an early Freemason (possibly initiated during his visit to London in 1670, when he presented his architectural drawings to Christopher Wren and Charles II). Nicodemus’s son, Carl Gustaf Tessin, recalled that his father was always proud to call himself a Master Mason, and he himself was considered the leading figure in Swedish Freemasonry. Swedenborg was a great admirer of Nicodemus’ architectural designs, and he would serve Carl Gustaf in several Franco-Jacobite diplomatic missions. When Yeats viewed Nicodemus Tessin’s palace, he realized it deserved “its great architectural reputation,” for he discovered “a vast, dominating, unconfused outline, a masterful simplicity,” which he believed expressed the essence of Swedish royalism and patriotism.

The dignity and attractiveness of the Swedish royal family, the lavishness of the ceremonies, and, especially, the glittering mosaics in the Golden Hall of the new City Hall sent Yeats into reveries about Ireland’s history and on-going struggle to become an independent nation. Inspired by his feeling that he was back in an 18th-century court, he planned to write a tribute to Sweden when he returned to Ireland. The biographer Roy Foster expressed surprise at the opening lines of Yeats’ essay The Bounty of Sweden, noting that it is “disconcertingly different from anything the reader may be disposed to expect.” The surprise was provoked by Yeats’ opening reference to “the Cabbalist MacGregor Mathers,” who had encouraged the young poet to write down his first impressions of Paris, for, like those of Stockholm, he would never see it so clearly again. However, the Swedish connection with Mathers’ Jacobite and Masonic fantasies would not surprise Ambassador Eric Palmstierna, who described Yeats in Sweden as the reincarnation of a Jacobite bard, “with strong hands accustomed to harp strings and clashing swords.” The Palmstierna family was aware that Swedish Freemasonry combined Kabbalistic with Swedenborgian symbolism in its rituals and that one could still become a “Stuart Brother” in a Swedish lodge. They also knew that the Swedish king, Gustav V, whom Yeats met and admired, served as hereditary Grand Master of Swedish Masonry—a Stuart tradition transmitted to Gustav III by Bonnie Prince Charlie. Gustav V’s son, the “artist prince” who worked with the stonemasons and lapidaries on the Golden rooms, was also an Écossais Freemason.

As the Yeats critic Giorgio Melchiori observed, the poet perceived in Stockholm and its new City Hall a “symbol of the holy city of art.” Thus, in 1926 Yeats tried to emulate the architectural and Masonic accomplishments of Nicodemus Tessin and the current Swedish royal family, when he urged the Irish government to bring artisans from Sweden to teach the Irish how to improve Dublin’s great public buildings. In The Bounty of Sweden, Yeats wrote that the Golden Hall carried his mind “backward to Byzantium.” [Do click here to get an eyeful of Golden Hall!] As Roy Foster wryly remarked, “Dublin could reach Byzantium by way of Stockholm.” But, certainly, it was Yeats’ memory of Stockholm’s glittering walls that enriched his earlier impression of Ravenna’s golden mosaics, and both fueled his imagination to produce the incantatory lines of Sailing to Byzantium:

O Sages standing in God’s holy fire,

As in the gold mosaic of a wall,

Come from the fire, perne in a gyre,

And be the singing masters of my soul.

In that same year, in January 1926, Yeats published his philosophic treatise, A Vision, noting that he could not have written it without his study of Swedenborg. Linking his memories of royalist Sweden with the neo-Jacobitism of his youth, he dedicated A Vision to MacGregor Mathers’ widow. Seven months later, in July, in Moina’s preface to a new edition of Mathers’ translation of the Kabbala Denudata, she reaffirmed her full belief in her husband’s Jacobite ancestry. Some literary critics characterize Yeats’ praise of royalist Sweden and tribute to the Mathers as a depressing foretaste of his sympathy for Mussolini’s early Fascism. However, it is more historically accurate to view them as the nostalgic aftertaste of the Jacobite dreams of his magical mentor, MacGregor Mathers, Comte de Glenstrae, who through Swedenborgian Masonic rituals was able to “feel like a walking flame,” when all tartaned up in flamboyant Highland garb.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)