|

| Grand Lodge of Ireland |

Following Sinn Fein’s electoral success two weeks ago, when it won 27 of the 90 seats of the Northern Ireland Legislative Assembly and is poised to lead that government for the first time since its inception in 1921, I thought it an apt moment to share a few pieces of political history from a century ago. Freemasonry was trapped amid the civil war between Nationalists and Unionists; Catholics and Protestants; neighbors and neighbors. Lodges were ransacked and burned, and the Irish Republican Army even commandeered the Grand Lodge headquarters in Dublin from April 24 to June 1, 1922. (The same building damaged by an arsonist last New Year’s Eve.)

I’ll get straight to the record, drawing from both Masonic and outside sources.

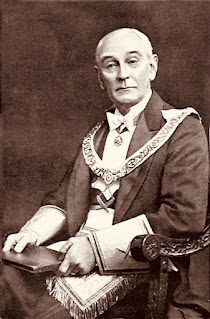

During the Grand Lodge of Ireland’s December 27, 1922 St. John’s Day Stated Communication, Deputy Grand Master Claude Cane summarized what had transpired at Freemasons’ Hall, Dublin:

What happened here in the South of Ireland during the past year, and especially in this house of ours, is so fresh within your memory, and has been so thoroughly dealt with in the report, that I need not elaborate it very much. You all know and will remember how on the twenty-fourth of April, this beautiful Hall of ours was suddenly invaded by a number of armed and lawless men, and taken forcible possession of. The occurrence was not wholly unexpected, fortunately perhaps, because I had heard warnings of it for some weeks before. I took upon myself, some six weeks before the occurrence actually took place, to remove all the archives and things which really mattered as far as the history of the Grand Lodge of Ireland was concerned from the doubtful security of our strong room and safes downstairs to a much safer place, a place where they were in absolutely perfect safety all through the trouble, and where they still remain. Naturally the current books, and things you were using every day, had to remain in the Hall and take their chance. But I am alluding more particularly to the old minute books and old records and things of that sort, belonging to the Grand Lodge ever since the year there first was a Grand Lodge in Ireland, nearly two hundred years ago, which would have been absolutely irreplaceable. These were all absolutely safe the whole time.

|

| RW Claude Cane |

As you may imagine, after the occupation became an accomplished fact, my frame of mind was not a very enviable one. I had to assume a very great deal of responsibility, and I felt that any wrong step on my part, or on the part of those with whom I took counsel, might lead to very much worse things than had already happened. I felt that anything would be better than having this building and all its contents destroyed; I felt that sooner than rush things, it was better to submit to what was an undoubted indignity, and a great pain and grief to all of us for some time rather than run the risk of seeing all that we held most sacred go up in flames and ashes. So for six weeks I, and others who were advising me, had to possess our souls in patience. So many Brethren gave me such valuable help during that time—with advice and work as well—that it would really be invidious to name anyone in particular, with the exception, I think, of one Brother whose work was not at an end when we got this Hall back, but to whom we all owe a very deep debt of gratitude for all he has done in restoring us to our possessions here, and that is your Grand Superintendent of Works, Brother G. Murray Ross.

I should like also to personally thank Brother Besson, of the Hibernian Hotel, for the very prompt way in which he came to our rescue and gave us the resources of his house and a room in which to establish a temporary office. It was a great advantage to us to only have to cross the street and to be saved from the trouble of looking out for someplace where the business of Grand Lodge could be carried on. Brother Besson was most accommodating and most kind to us all through that time.

I am bound to say that during all the negotiations carried on with the view of getting this building restored to us, I was treated with the very greatest courtesy and consideration by those members of the Provisional Government with whom I came in contact. They seemed to realize fully what our Order is. I am speaking particularly now of two men who are no longer living, no longer in the government: Mr. Michael Collins and Mr. Arthur Griffiths. They seemed to realize that, so far from our being a dangerous body, we were a body, as we are, bound to support, and give all the assistance we can, to any legally constituted government of the country in which we live, and that we are entirely deserving of the support of that government. When I found that they were in this frame of mind, I must say that a great load was lifted from my mind; I felt that we in our future, once law and order were established in Ireland, would be assured, and I believe that it will be so. No government with any sense at all can fail to recognize that a body composed as we are, and holding the principles that we do, and taught, as we are taught, in our ceremonies and ancient charges, can be anything but a source of strength to any reasonable government.

At the same time I wish to remind you again, as I did last year, that it is our bounden duty, not as an organization, because we are forbidden to act as a political organization, but as individual members it is our bounden duty as Masons to be good citizens and to support the Government under which we live, so long as that Government protects us. Both here in Southern Ireland, and in Northern Ireland, where there is a different Government, that applies.

It is a very bright spot in our future outlook to find how thoroughly in accordance with us our Brethren in the North are. Whatever divisions otherwise may happen in Ireland, there is not the slightest prospect, at present at any rate, of any division between the Masons of Northern Ireland and the Masons of Southern Ireland. The Masons of Ulster, equally with the Masons of Dublin and the South have one great common heritage: the Grand Lodge of Ireland. The Grand Lodge of Ireland is the Grand Lodge of Ireland, not of any particular section of Ireland. As long as it remains the Grand Lodge of Ireland, it ranks as the second Grand Lodge in the world, and in point of everything except a few years of age, I think we can claim full equality with the mother Grand Lodge of the world, England.

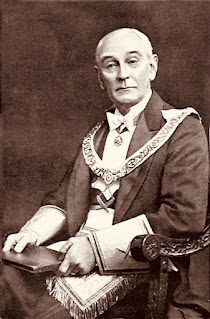

Grand Secretary Henry C. Shellerd expanded on the subject. Excerpted:

In many parts of the country, the buildings used for Masonic purposes were wrecked by irresponsible individuals, who seemed to delight in the destruction of all sorts of property not adequately protected. The Grand Master, in the wise exercise of his discretion, prohibited the meetings of the lodges in all the Provinces of Southern Ireland for a considerable part of the year. During the past three months, however, a better spirit seems to have prevailed, and the exercise of the discretionary power granted to Provincial Grand Masters to permit lodges to meet, has so far been attended by no unpleasant incidents. That the Dublin Freemasons’ Hall has been handed back to the Order without any wanton injury to the edifice or its contents is an indication that there is no special hostility to our Order in the Metropolis.

|

| RW Henry C. Shellerd |

The fact that the annual returns from lodges in the South and West of Ireland are reaching headquarters daily proves that the lawlessness which was rampant some months ago is being steadily brought under control, and that our Brethren in every part of the country, North and South, are acutated by an intense desire to uphold the Great Principles of Peace and Goodwill with which our Order, throughout its whole history, and in every part of the world, has been so closely identified.

Beyond Dublin, matters were not as amicable. The Spectator, in its June 3, 1922 edition, reports:

Many Masonic halls have now been destroyed, one of the first to suffer being that at Ballinamore. In Mullingar the Masonic Hall was raided, and all the windows and presses were smashed. Petrol was poured over the broken furniture, and the complete destruction of the place was prevented only by the intervention of the local priest. In Dundalk, which is not very far from the Ulster frontier, there were three Masonic lodges with a fairly large membership. Their hall was raided and the books and other property seized. Many of the members received a few days’ notice to leave the town, and some of them had to escape hurriedly to Belfast. As a consequence of these proceedings the meetings of these lodges have been indefinitely suspended. … No man residing in the “Irish Free State” whose name appears on the roll of the Grand Lodge of Freemasons of Ireland can, at the present time, have any sense of security for himself or his family. He can only look to his brethren in Great Britain to use their influence with the British Government on his behalf. The preservation of life and property is not a matter of party politics; it is an elementary principal of any Government, and it is the absolute duty of the British Cabinet to see that it is maintained in Ireland.

The Builder, one of the great Masonic periodicals of early twentieth century America, includes letters to the editor in its September 1922 issue that tell more. Right Worshipful Claude Cane, the Deputy Grand Master from the paragraphs above, writes in part in a letter dated May 30: “I do not believe there is any general hostility to the Order in Southern Ireland, nor do I believe that any feeling of the sort is encouraged by the Roman Catholic Church, which fully appreciates the difference between Irish Freemasonry and that carried on by the so-called Continental Grand Lodges, which reject our first and principal great Landmark, and consequently are not recognized by us.”

A Bro. George A. Anderson of Pennsylvania writes: “A large number of the Masons in America do not know how conditions are in Ireland, neither do they know the real cause of it all, and I think they should know.” He also included a letter from Bro. W.J. Allen in Belfast who says:

The condition of things over here has not improved very much of late, except that there are not so many shootings in our own city. … The Masonic Halls are being raided, and in many cases destroyed. The Grand Lodge premises in Dublin are at present in the occupation of the I.R.A. There was a curious result of that the other day.

We were starting a new preceptory in Belfast in connection with our lodge and had applied for a warrant. Before the warrant could be issued the premises in Dublin has been seized, and all the forms were kept there. The Masonic authorities had to get a copy of the latest warrant issued, and from this they made a fresh copy all in the writing of the Grand officer. This warrant was used last Saturday and is in the possession of our Registrar. The Masonic authorities here, for some reason or other, do not want to appeal to Freemasons outside or to make “political capital“ of the seizure, but I think it would be well if the Freemasons of America were freely told of the campaign that is going on against the Order in Ireland. Perhaps you could help a little in this in a quiet way among your own associates. There was one man, whom I know personally, who had a narrow escape in the recent murders in County Cork. He is a Methodist clergyman, and was in one of the houses that were visited. He escaped from bed in his nightshirt and got away into the fields. It was the middle of April and the weather was very cold at the time. Three or four others were shot dead the same night. His brother is a member of my lodge, is Registrar of my chapter, and first Preceptor of the new preceptory. He is a past Provincial Senior Grand Warden of the Province of Antrim. That is the Masonic province of course, which is practically the same as the ordinary County of Antrim.

A clipping from the May 18 edition of a Belfast newspaper also was provided to The Builder. It reads, in part: “Recently one of the South of Ireland gun clubs issued a statement boasting that they were going to compel all Freemasons and Unionists in the ‘Free State’ to supply food, clothing, and housing accommodation to Roman Catholic unemployed. Their fellow ruffians had for a long time been burning down Masonic and Orange Halls and persecuting Freemasons along with other Protestants.

|

Richard Hely-Hutchinson

Sixth Earl of Donoughmore |

“The continuance of these outrages, which there is no evidence to show the Free State forces now responsible for law and order ever tried to stop, has caused the Earl of Donoughmore, Most Worshipful Grand Master of Irish Freemasonry, to issue an order suspending all meetings of Masonic lodges in Southern Ireland.”

To conclude, I draw from the January 1923 issue of The New Age Magazine, published by the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite, Southern Jurisdiction. It quotes from the October 7, 1922 edition of The Northern Whig and Belfast Post story “Masonry in Ireland,” which covered the previous day’s annual concert in Ulster Hall benefiting Masonic charities. The Provincial Grand Master’s remarks were relayed:

He thanks those present for their attendance there that evening, not so much for the pecuniary support for the object for which the concert was being held—that was their Masonic charities—but for the moral support they gave to the Order by their presence there. In those days he must say that Freemasonry needed all the support it could get not only from those inside the Order, but from its many friends outside the Order.

Freemasonry in Ireland has been coming through very difficult times. Their halls had been raided and burned, and their brethren in many cases had been ill-used in other parts of Ireland. Scandalous and scurrilous charges had been brought against their Order. He did not say their Order was perfect. It was, after all, only a human institution, and no human institution was perfect—not even their churches and their ministers, who perhaps ought to set the highest standard—so Freemasonry could not claim perfection, but it was strange that the charges that were brought against them were chiefly under two heads, on which they were absolutely guiltless.

First of all the charge was made that Freemasonry was a political society, but if there was one thing above all other that was never mentioned inside the walls of the Masonic lodge, and that was absolutely barred by the laws of their Order, it was anything in the nature of politics. They were also blamed for being an irreligious society. They were perhaps irreligious in a sense because the word religion was unfortunately too often mixed up—and oftener in Ireland perhaps than anywhere else—with sectarianism. Freemasonry was absolutely nonsectarian, and it was a calumny to say that any Order whose fundamental tenets were the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man was an irreligious Order.

It is Anderson’s Constitutions of 1723 whence modern Freemasons receive our charges to be good, and religiously circumspect, citizens where we make our lives. “A Mason is a peaceable Subject to the Civil Powers, wherever he resides or works,” it reads, “and is never to be concern’d in Plots and Conspiracies against the Peace and Welfare of the Nation, nor to behave himself undutifully to inferior Magistrates.…”

|

| My copy of Anderson’s, printed in 1924. |

The First Charge, the most famous one, titled “Concerning God and Religion,” states:

A Mason is oblig’d by his Tenure to obey the moral law, and if he rightfully understands the Art, he will never be a stupid Atheist nor an irreligious Libertine. But though in ancient Times Masons were charg’d in every Country to be of the Religion of that Country or Nation, whatever it was, yet ’tis now thought more expedient only to oblige them to that Religion in which all Men agree, leaving their particular Opinions to themselves; that is, to be good Men and true, or Men of Honour and Honesty, by whatever Denominations or Persuasions they may be distinguish’d, whereby Masonry becomes the Center of Union, and the Means of conciliating true Friendship among Persons that must have remain’d at a perpetual Distance.

In a free and peaceful society, this is done effortlessly, but when domestic tranquility is imperiled I imagine one requires disciplined application of all Four Cardinal Virtues—with innate reliance on the Theosophical Virtues as well—to remain steadfast.

(In medieval England, the various Statutes of Laborers regulated masons’ qualifications, remuneration, ability to meet, and other details, but the statute of 1405 specifically compelled such workers to take an annual oath to comply with the law.)

Perhaps the condition of Freemasonry today is not ideal in instances. Could be the content of lodge meetings isn’t exactly how we prefer it; or maybe the size of the membership remains a worry; or some may think their grand master is a fink—but things have been, and can be, far worse.