|

| New Testament in Middle English — Published in England at the end of the 14th century by John Wyclif, this is a vernacular translation, and after it gained some popularity it was suppressed by church and royal authorities opposed to vernacular Bibles. Wyclif (1330-84) was an Oxford scholar, diplomat, and reformer. |

|

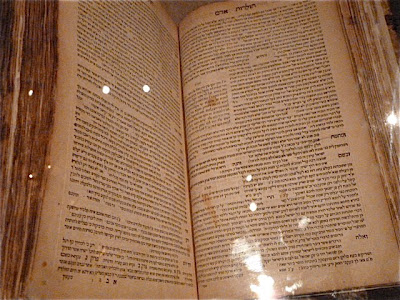

| Judaism in the New World — This is a prayer book for the Sabbath, Rosh Hashanah, and Yom Kippur, published in New York by John Holt in 1766, based on a translation by Isaac Pinto. While London in 1766 was home to the largest English-speaking Jewish community, this first English translation of the Hebrew prayer book was printed in British Colonial New York City. Translator Isaac Pinto writes: 'It has been necessary to translate our Prayers, in the Language of the Country wherein it hath pleased the divine Providence to appoint our Lot. In Europe, the Spanish and Portuguese Jews have a Translation in Spanish, which as they generally understand, may be sufficient, but that not being the Case in the British Dominions in America, has induced me to attempt a Translation in English.' |

|

| A Bible for Native Americans — Published in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1663, this Bible was intended for the conversion to Puritan Christianity of the native people near the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Algonquin Indians. It also served the purpose of showing the authorities back home in England how their funds were being used. |

|

| The Koran in Federal America — You may have noticed I have chosen to spell Koran thusly. It's just a preference for simplicity. In Federal America (c. 1790-1830) the standard English spelling was Alcoran. This book was published in Massachusetts in 1806, and is based on the London version of 1649. Shown here is Sura 22, concerning the pilgrimage to Mecca. |

Illustrated Guide — To explain Jewish ceremonies of the Temple period to Christians, woodcuts were made, such as these depicting the Altar of Burnt Offerings and the High Priest in full ceremonial vestments. These pages are within the first Calvinist vernacular Bible printed in Poland, 1563. This particular copy was owned by Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex (1773-1843), son of George III of England.

The Apocalypse of Saint John, from either Germany or the Netherlands, c.1465. Published for the illiterate, this book combines color pictures with text to allow a literate reader familiar with Revelation to share the story with those who could not read. The technology, frankly remarkable for the mid 15th century, is called blockbook. It derived from textile printing, and was used even after the invention of movable type. Words and pictures are transferred by manual pressure on the blank reverse of each page, the face of the page having been placed on an inked woodblock or woodblocks.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse — One of 15 woodcuts by Albrecht Dürer, Nuremberg, 1522. The individual import of each horseman—War, Famine, Pestilence, and Death—is debated even today, but this is the image of them that permanently impressed itself upon the public imagination.

The Gutenberg Bible. Again, what can you say? The appearance of the Christian Bible in print marked the great achievement of the second millennium of the Common Era. The mechanical reproduction of St. Jerome's translation into the Latin Vulgate, the standard text in the language universally accessible to the literate of the period, heralded a new age and the wide dissemination of this version, from which so many others would flow.

Tetro Evangelie (Moscow, 1606) is a printed edition of the four Gospels in Church Slavic. Lavishly illuminated by hand in gold and colors, it reflects the "Orientalism" of 17th century Muscuvite design. This illustration, enlarged below, depicts St. John, inspired by divine revelation, dictating his Gospel to Saint Prochoros.

A wonderfully preserved copy of the Bay Psalm Book, Massachusetts, 1640. Named for the Massachusetts Bay Colony, it is the first book printed in English in America. To say its style is plain would be an understatement; in keeping with the monochromatic lives of its Puritan creators, the book uses types brought from England, but does so without any discernible order. However, it is the first to employ Hebrew type in America, denoting a scholarly motivation among the Puritans.

The Good News in Africa

—

Published by American missionaries in west-central Africa in 1879, this St. John's Gospel is printed in the Dikele language of the Bakele people. A Reverend Preston, in a letter dated January 1865, revealed how he had translated John's Gospel into Dikele years previously, but it is not known if this is a product of his work.

Title page of a small Jewish prayer book named Small Offering. The title alludes both to the book's own diminutive size and to its popularity as a parting gift to travelers. The text went through several print runs during the mid 19th century in America, as tens of thousands of Jews fled central Europe. This copy is dated 1860.

Found in translation: The word targum means translation in Aramaic, and usually is used to refer to the Aramaic translation of the Hebrew Bible, known as Targum Onkelos. This small Pentateuch was designed specifically to allow for the fulfillment of the Talmudic dictum that each individual read the weekly Torah portion twice in the original Hebrew, and once in Aramaic.

The first Bible printed in Spanish, 1553. The Ferrara Bible was based on the Ladino version of the Tanakh used by Sephardic Jews at a time when Jews were not permitted to live as Jews in Spain. Their choices were conversion to Christianity or expulsion from the land. Many opted to keep their faith to themselves while living outwardly as Christians; one version of the Ferrara was printed for Christian readers.

A Hebrew-Yiddish glossary from 1604, titled A Good Lesson. It is arranged in order of the sequence of Biblical texts. Shown here on the left are terms from the opening of Proverbs; on the right is a polemical work by David Kimhi (c.1160-1235) refuting Christian interpretations of the Hebrew Bible.

The Bible in Japanese, published in 1955. Bibles in Japan and the rest of Asia were nothing new by the mid 20th century, although in Japan, toleration of Christianity varied between persecution and some acceptance between the 16th and 19th centuries. After the Second World War, with a national constitution penned by the American-occupation government, Christianity gained actual popularity.

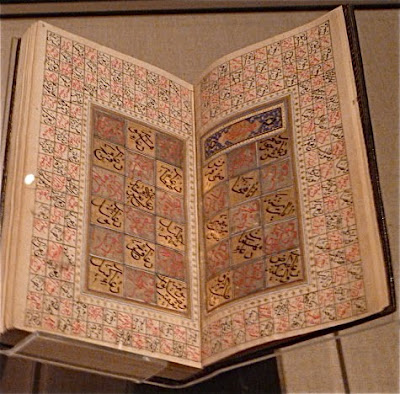

Epithets of God — From 18th century Iran, this selection of texts was compiled for the use of religious students more comfortable with Persian than with Arabic. The traditional epithets of God, recited as a devotional exercise, are given in both languages, and also are rendered numerically.

More from al-Nayrizi

—

The calligrapher of this book of prayers also was Ahmad al-Nayrizi. The book, from mid 18th century Iran, contains prayers for every day of the week, and is open here to Friday and Saturday.

Anthology of Suras and Prayers from Iran, 1732. The work of Ahmad al-Nayrizi again. Features prayers in Arabic partially translated into Persian. This duality offers the user prayers appropriate to a wide variety of personal circumstances.

Epithets of the Prophet, Medina, Arabia, 1847. Manuscripts devoted to praises of the Prophet were created for personal use in many parts of the Ottoman Empire. This copy of Dala'il al-Khayrat is a handsome example of such. It is open to a list of names by which the Prophet may be addressed, which often is recited as a litany.

Manual of Divination, from North Africa, 17th century. This contains two medieval Hebrew treatises on the geomantic arts. Geomancy is the practice of divination by means of interpreting a series of dots or points. In standard geomantic practice, 16 different configurations are arrived at by the construction of four horizontal rows, with each element consisting of one or two dots, based on the outcome of a particular chance procedure. The patterns are analyzed, often in conjunction with astrological charts, to allow the practitioner to ascertain the answer to a yes or no question, or to decide between alternatives. (The Biblical prohibition against divination is circumvented by the addition of a layer of mathematical calculation in determining the outcomes.)

Ashkenazic Mahzor — The spread of Judaism around the world results in different prayer rites for different Jewish communities. Ethiopia, China, India, Brooklyn. Though they share the same essential contours, the rites reflect local customs and traditions. Developed in France and Germany, the Ashkenazic rite spread across central and eastern Europe. The architectural gateway shown here frames the text "Who opens the Gates of Mercy," an especially resonant theme during the period between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur.

And an Italian Mahzor, from the late 15th century. Jews lived in Italy since at least the 2nd century BCE. Due to its geographic centrality, Italy served as a point of intellectual contact between Jewish communities as far east as Babylon and as far west as the Iberian Peninsula. Italian Jewry had the Roman rite, which combined several distinct modes of prayer, including the Ashkenazic rite, the Sephardic rite, and that of Greek-speaking Jews. The tree depicted here represents the bitter herbs of the Passover Seder liturgy, and is the only known use of a tree to depict the maror.

Altar Gospels, with gilt binding, from the reign of Catherine the Great. The binding is the work of French-influenced Muscovite craftsmen in 1795. It intentionally draws attention to the Word of God and signals the importance of the Gospels. This text would be placed on the church altar during divine liturgy, and would have been held aloft for the congregation to see prior to that day's Gospel reading, ergo its alternate name: Elevation Gospels. The magnificent binding is heavily gilded silver, with five enameled miniatures in surrounds of green semiprecious stones. Christ, at center, is depicted as a Russian bishop, and the four Evangelists occupy the corners. Not seen here are the clasps, which represent Saint Peter and Saint Paul.

Phoenix and Sun: Beneath a crest evoking the phoenix and sun imagery associated with the Amsterdam Sephardic community is the signature of the artist: "Rephael Montalto created this in 1686." The emblem is supported by two mythical female creatures comprising a hybrid of human and plant forms similar to those depicted along the borders of the scroll. They also hold a fleur-de-lis, closely associated in the public consciousness with France, in recognition of Rephael's grandfather, Elijah Montalto, who served as physician and advisor to Marie de Medici, Queen of France.

I shot more than 150 photographs, but you get the idea. This was a once-in-a-lifetime (at best) opportunity to enjoy centuries worth of treasures. I hope you enjoyed this too brief pictorial.