Freemasons living in a free society know that the privacy maintained around lodge work exists for a number of very important, but relatively harmless, reasons. First, the degrees are used to set a state of mind in the candidate that is conducive to the learning of lessons not just on a level of logic, but at a level of emotion. By clouding the degrees in mystery, the candidate approaches the degree ceremony with a pre-existing state of wonder, which intensifies the overall experience, and hopefully establishes the lessons firmly on his conscience.

Second, Masons maintain privacy because of tradition, and frankly, Freemasonry values tradition sometimes just for the sake of tradition. In the case of the ritual, the tradition had long been that the ritual was taught mouth to ear, and not written down, not even in cipher or code. This practice existed to a large extent because of the limitations of literacy in eighteenth century Europe. On the other hand, privacy also existed to maintain the mystique, and thereby the impact, of the ritual. But from early on, probably from the morning after the first Masonic lodge meeting, people have been writing accounts of what they suspected took place during Masonic degree ceremonies.

The practice of “exposing” Masonic ritual developed into a genre of Masonic literature called “exposures.” Masonic exposures gained popularity in the mid eighteenth century, featuring the full texts of lectures, recounted by “genuine and authentic past members” of some Masonic lodge or, later, concordant order. Exposures were often published to discredit Freemasonry, or to serve as documentation for charges of Masonic involvement in political, religious, and social subterfuge. The content of Masonic exposures often included material of dubious accuracy, perhaps to further the agendas of the publishers. For example, an exposure might include a script in which Masons say sacrilegious or treasonous things, intending to embarrass or indict Freemasonry.

Here in America, we are most familiar with the exposure credited to William Morgan from the early nineteenth century, the preparation of which led to his disappearance, and to a problematic time for the Craft. But Morgan’s book, and later versions, borrow liberally from exposures printed across Europe throughout the mid and late eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century.

The Livingston Masonic Library has always included among its thousands of books a substantial collection of Masonic exposures. The contents of exposures are generally of questionable accuracy, partly because of the sensationalist motives of the authors or publishers, but also because of the fact that Masonic rituals vary depending on time and geography. However, exposures are often the only written sources of information about the rituals from centuries past.

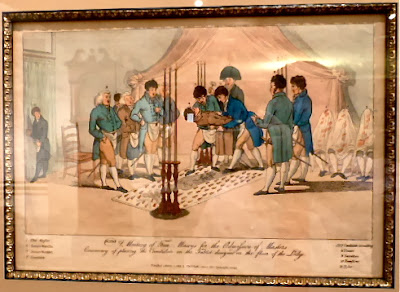

The engravings on display represent a series of seven illustrations of a variation that first accompanied Le Catechisme des Francs-Macons, an exposure printed in 1745, credited to French writer Louis Travenol under his alias Leonard Gabanon. The original illustrations in Gabanon’s book depicted the men in the garb of France in the 1740s. Our engravings date from 1809-12, and feature variations in the clothing and manner of dress of the individuals shown.

If you watch cable television, you will be familiar with the style and composition of Gabanon’s illustrations, since they are often used in documentaries exploring the history and symbolism of Freemasonry. The illustrations are provocative, in the sense that they cause Masons to reflect on what degrees might have entailed in Europe more than two hundred years ago. They may cause the general public to be curious and interested about the nature of Masonic ceremonies, just as the same images caused curiosity and interest when published throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. We may never know if they are accurate representations of Masonic ceremonies of the eighteenth century. As with many things Masonic, we are left to wonder, question, and interpret, perhaps never to know the “true” answer.

No comments:

Post a Comment